I’m a simple person, not flamboyant. I don’t like showing off or going out, only with my partner or a friend. As a young person I didn’t understand why I had feelings for men. It made me shy and lose my confidence. It made me stop wanting to be close to my friends and I became a person of solitude. Not because I wanted to be, it was really difficult. I just saw I was different. I thought I was the only person with this problem. On the street I was constantly aware of all eyes on me. Pretending all my life not to be me. On the bus, with my family, in my own house even. I don’t judge people who end their lives, it’s not an easy life.

Back in Nigeria as a lawyer I tried to make a change with openminded lawyers and organizations. But Nigeria is a big country full of lawyers and even gay politicians don’t vote for gay rights. All I can tell my people, is to hold on and to leave the country. Being gay in Nigeria is like living in a cage. Being LGBT there is illegal. Living with another man is illegal, rallying is illegal, an LGBT meeting is illegal, attending a gay marriage, helping a gay person, contributing money to an LGBT organization. According to the law, the punishment for being gay is jail term up to fourteen years, but jungle justice usually results in death. There’s this trend happening on gay dating apps of keeping gay people hostage and blackmailing them over their sexuality, as a business. I’ve seen people being beaten up, being burnt alive. It’s a terrible thing to be gay in a homophobic country.

But I’m here now, happy, safe and free, living in my private apartment. Before I lived in different refugee centers, there you’re not free. It’s weird, I came here for safety, but these centers are horrible, demoralizing and depressing. You have people from different cultures, educational backgrounds, professions, sexualities and beliefs. Gay, homophobic, they treat you like a non-entity.

Here it’s not all perfect, it’s not that people here don’t discriminate, for example because of your color. I didn’t experience it myself yet, but I hear the complaints around me. The fact that Respect2Love (R2L) is bicultural, encompasses people from all continents and all walks of life, makes it different from the rest of COC. People who aren’t recognized in the white scene are being seen at R2L. I recommend queers of color to find a place like that, it’s important to have a community. There were times I felt lonely while waiting for my residence permit, but I didn’t lose hope because of the R2L community.

Now I have a place in this foreign land, I can call home. Before I got to know R2L, I’ve been with Rainbow Anonymous, I’m still there at present. It’s a safe space for LGBT refugees set up by one of us, without homophobes. R2L is a bigger organization, there’s people who mentor us, who taught me a lot about leadership, empowerment and resilience. As a foreigner you don’t know much. Now I know I’m not alone and not the only black person in the community. I know that I can get help in hostile situations and where to get it.

Knowledge is power. Knowledge gives confidence. When people know who they are and their history, it helps to emancipate them. For a lot of LGBT refugees of color who lived in shame and fear all their life, it takes a while to come out as LGBT and adapt to another life here. We should nationalize R2L, to help empower more people. We should also mix into these all-white COC spaces, to bring white, black and brown people together, to empower the community. There’s strength in unity.

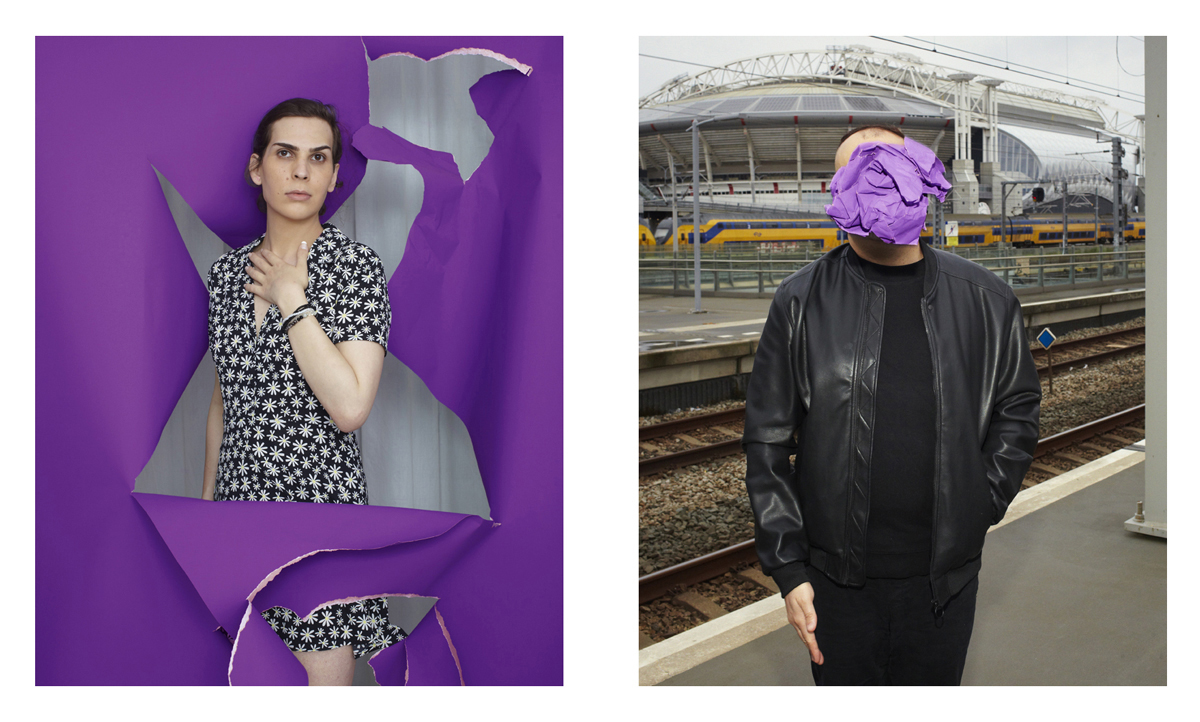

The opening in my portrait signifies that the veil that was covering me before, has opened. I can see clearly now. I am no longer hiding now. I am stepping out in the light with pride. Full force. I am stepping out.